Note: This paper was written as an assignment for a medical communications course in 2004. I’ve published it here after receiving several requests that I do so. It needs to be updated, but I haven’t had a chance to do the research in order to do so.

Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is a debilitating neurological disorder characterized by chronic widespread pain and fatigue. It affects approximately 2% of the population and is more common in women than in men. Central nervous system sensitization affects the entire body, leading to many secondary symptoms. This paper will cover the history, symptoms, and causes of FMS as well as recent research and known treatments for the syndrome.

Description

Fibromyalgia has been described as a full-body migraine. Another common explanation is to compare everyday life with FMS as being similar to the aches and pains associated with a severe case of influenza.

FMS patients experience intermittent flares, which are episodes of increased symptomology. Flares usually occur in response to physical or emotional stress—a schedule change, an illness or injury, a new job, the birth of a child, etc. While fibromyalgia is not considered a degenerative disorder, its symptoms usually become more severe if the patient also has a degenerative disorder such as arthritis.

Diagnosis

First, a patient must have experienced continuous pain in all four quadrants of the body for at least three months (Wolfe et al., 1990). Doctors will usually order many different tests in order to rule out arthritis, Lyme disease, and other conditions that might be confused with fibromyalgia.

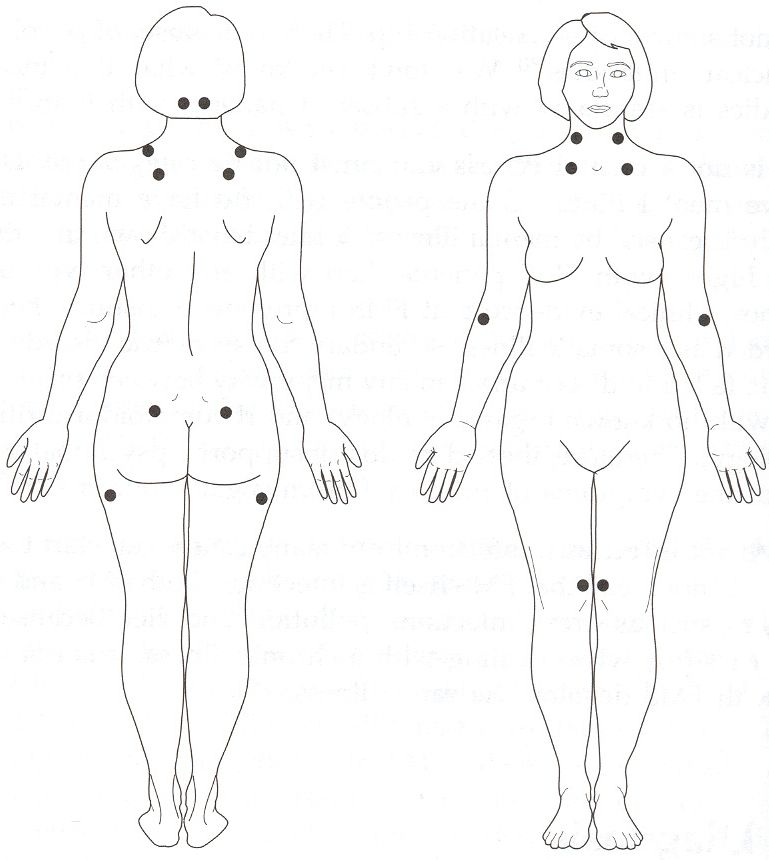

The key diagnostic tool for FMS is the tender point exam. No more than 4kg/1.54km2 of pressure is applied to 18 specific points (see Table 1). If there is significant pain in at least 11 of the 18 points, the patient may be diagnosed with fibromyalgia.

| Table 1: Tender Point Sites (Wolfe et al., 1990) |

|---|

| Occiput: bilateral, at the suboccipital muscle insertions. |

| Low cervical: bilateral, at the anterior aspects of the intertransverse spaces at C5–C7. |

| Trapezius: bilateral, at the midpoint of the upper border. |

| Supraspinatus: bilateral, at origins, above the scapula spine near the medial border. |

| Second rib: bilateral, at the second costochondral junctions, just lateral to the junctions on the upper surfaces. |

| Lateral epicondyle: bilateral, 2 cm distal to the epicondyles. |

| Gluteal: bilateral, in upper outer quadrants of buttocks in anterior fold of muscle. |

| Greater trochanter: bilateral, posterior to the trochanteric prominence. |

| Knee: bilateral, at the medial fat pad proximal to the joint line. |

There are so many common secondary symptoms that it is not unusual for a patient to be treated by multiple specialists for those symptoms over a period of years before she is diagnosed with FMS. Secondary symptoms need not be present for diagnosis and will vary from one patient to the next.

| Table 2: Secondary Symptoms | |

|---|---|

| Migraine or tension-type headaches | Temperomandibular joint disorder |

| Irritable bowel disorder | Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Impaired memory and concentration | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Restless leg syndrome and other sleep disorders | Sjogren’s syndrome |

| Raynaud’s phenomena | Periodic muscle spasms and cramps |

| Myofascial pain syndrome | Impaired coordination |

| Intermittent hearing loss or ringing noises | Skin sensitivity, itching, burning |

| Insomnia | Interstitial cystitis |

| Dizziness | Chemical sensitivity |

| Sensitivity to light, smells and sounds | Fatigue |

| Costochondritis | Diffuse pelvic pain |

| Nausea | Dyspareunia |

| Rashes | Dermatographia |

| Chronic sinusitis/post-nasal drip | Eye irritation, burning or dryness |

History

“The night racks my bones, and the pain that gnaws me knows no rest,” laments Job (The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version, Job 30:17). It’s easy to imagine that Job suffered from FMS.

University of Edinburgh surgeon William Balfour described fibromyalgia, which he called rheumatism, in 1815 (Balfour, 1815, as cited in Starlanyl, 1999). Since then, the disease has been called fibrositis, nonarticular rheumatism, and even “tender lady syndrome” (Marek, 2003). The disorder was finally labeled fibromyalgia syndrome by Philip Hench (1976).

The American College of Rheumatology published its criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia in 1990 (Wolfe et al.). The American Medical Association accepted the criteria in 1987, followed by the World Health Organization in 1992 (WHO, 2004).

Cause

After almost two centuries of study, the etiology of fibromyalgia is still a matter of much debate. There are no lab tests for FMS. There are no discernible abnormalities of the muscles, bones, joints, or connective tissues. It is known to involve central nervous system changes (Starlanyl and Copeland, 2001), but those changes may be caused by or be the cause of the disorder. Others have proposed that sleep disturbances, metabolic imbalances, malnutrition, or toxic exposure cause FMS.

For the last 25 years, most practitioners have treated FMS as an autoimmune disorder, similar to arthritis. Levels of antinuclear antibodies are used to diagnose autoimmune disorders, but the presence of those antibodies is similar in most FMS patients and healthy controls (Starlanyl & Copeland, 2001).

Travell and Simons believed that untreated myofascial trigger points caused fibromyalgia (1999, as cited in Davies, 2001). Trigger points, though, refer pain to different parts of the body. Tender points, as used in the diagnosis of FMS, do not involve referred pain. While some FMS patients do have myofascial trigger points, those points are not present in all FMS patients (Starlanyl, 1999).

Some doctors persist in believing that FMS is a psychiatric disorder, but researchers have been unable to distinguish between FMS, rheumatoid arthritis, and other patients who experience chronic pain using psychiatric techniques (Starlanyl & Copeland, 2001). Some physicians have reclassified fibromyalgia as a “functional somatic syndrome,” claiming that it is characterized more by disability than medical explanation, suggesting behavioral and psychiatric treatment rather than any other therapies (Barsky & Borus, 1999). While the incidence of psychiatric disorders such as depression is no higher in patients with FMS than in those with other chronic pain disorders, the number of fibromyalgia patients who have experienced acute or long term trauma or abuse is far higher than that of the general population (Romans et al., 2002 and Van Houdenhove et al, 2004).

Research

In the last ten years, several new technologies have been used to prove that FMS is a physical disorder. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and single positron emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans of FMS patients’ brains show significant abnormalities in regional cerebral blood flow (Graceley et al., 2002 and Mountz et al., 1998). FMRIs also demonstrate significantly increased activity in pain-relevant areas of the brain in response to stimuli when compared to a control group (Cook et al., 2004). Italian researchers have found elevated levels of the neuropeptide substance P, which is involved in the perception of pain, in the spinal fluid of FMS patients (De Stefano et al, 2000). Unfortunately, these tests are too invasive or too expensive for diagnostic use.

Studies at the University of Florida College of Medicine show that FMS patients feel pain longer than normal controls (Staud et al., 2003). One of the researchers, Roland Staud, also found that once a subject with fibromyalgia is exposed to painful stimuli, that patient stays more sensitive to further stimuli. Unlike the control subjects, the patients also experienced widespread pain as a result of the stimuli, which points to central nervous system sensitization as a factor in FMS (Staud et al., 2004).

Van Houdenhove et al. cite multiple studies regarding the effect of long-term stressors on the central nervous system in various mammals, including humans.

Human studies also suggest that the cumulative effects of physical or psychosocial burden may increase susceptibility to stress in later life, either through sensitization or failed inhibition of the HPA-axis, possibly due to glucocorticoid-related hippocampal damage. For example, retrospective studies have shown that emotional, physical or sexual abuse during childhood may not only increase future risks for anxiety, depression and somatisation, but even organic diseases such as coronary disorders, CVS, diabetes, CPOD and viral infections—which may be related to lifelong hyperreactivity of the LC-NE and HPA axes. (2004, p. 268).

Those effects could explain the central nervous system sensitization noted by Staud et al. Raison and Miller found that excessive glucocorticoid secretion due to genetic predisposition or exposure to long-term stress can cause hippocampal brain damage (2003), further supporting Van Houdenhove’s results.

Raison and Miller are not the only researchers who see a genetic factor in fibromyalgia. Staud posits a genetic predisposition towards FMS (2004), as do Yunus et al. (1999) and Pellegrino et al., 1989. Van Houdenhove, however, points out that generational behavioral cycles, such as those often seen in abusive families, could explain some of the apparent heredity (2004).

Treatment

Most treatment of FMS is limited to the management of symptoms. Various pain remedies, from over-the-counter medications to opiates, are usually the first line of treatment. Muscle relaxants, physical therapy, and massage help some patients. Trigger point therapy and injections are other possibilities. Many FMS patients experience difficulties in achieving restful sleep, so physicians commonly prescribe sedatives and tranquilizers. Low doses of anti-seizure medications and atypical antipsychotics, such as Requip and Seroquel, have been found to be effective in helping some fibromyalgia patients to achieve restorative sleep.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, and other medications that affect neurotransmitters help some fibromyalgia patients (Marek, 2003). Cymbalta, a new medication that inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake, seems to improve pain and reduce the number of tender points in FMS patients (Arnold et al., 2004).

Acupuncture and biofeedback have been found effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia (Ebell and Beck, 2001). Gentle, non-aerobic exercise such as Tai Chi and some forms of yoga may help patients, as well.

Stress reduction is one of the most important factors in improving the quality of life for fibromyalgia patients (Williamson, 1998). Regardless of whether the disorder is caused by stress or not, it is aggravated by stress. While it is impossible for any person to completely avoid stress, it is possible to reduce exposure to known stressors and learn to better cope with those that must be endured.

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs are relatively new in the treatment of fibromyalgia in the US. In Full Catastrophe Living, Jon Kabat-Zinn defines mindfulness as, “the complete ‘owning’ of each moment of your experience, good, bad, or ugly” (1990, p. 11). The theory is that mindfulness can allow patients to reduce their reactions to stress, improving their ability to cope with stressors. “In developing the capacity to step back and observe the flow of consciousness, mindfulness can shortcircuit the fight or flight reaction characteristic of the sympathetic nervous system, allowing individuals to respond to the situation at hand, instead of automatically reacting to it on the basis of past experiences.” (Proulx, 3002, p. 201) MBSR programs typically last from 8 to 12 weeks and include instruction in meditation, breathing techniques, physical awareness, and yoga. They often utilize journaling and group discussions regarding attitudes and positive thinking. While MBSR participation does not necessarily lead to improvement of the physical symptoms of fibromyalgia, it can lead to improved quality of life for the fibromyalgia patient.

Conclusion

It is unlikely that a cure will be found for fibromyalgia as long as its etiology is not fully understood. Even as the contributing factors are identified, though, the complexity of the syndrome leads one to believe that it is unlikely that any one treatment will provide a panacea. The progress made in the last fifteen years, though, has led to the reclassification of the disease and improved treatments, leading to an improved prognosis for all fibromyalgia patients.

References

Arnold, L. M., Crofford, L. J., Wohlreich, M., Detke, M. j., Iyengar, S., & Goldstein, D. J. (2004, Sep). A Double-Blind, Multicenter Trial Comparing Duloxetine With Placebo in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia Patients With or Without Major Depressive Disorder. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 50(9), 2974-2984.

Balfour, W. (1815). Observations on the Pathology and Cure of Rheumatism. Edinburgh Medical Surgical Journal (Edinburgh), 15, 168-187.

Barsky, A., & Borus, J. (1999, 1 Jun). Functional Somatic Syndromes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 130.

Campbell, B. (2004). The CFIDS & Fibromyalgia Self-Help Book(2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: The CFIDS/Fibromyalgia Self-Help Program.

Clauw, D. J. (1995, 01/09). Fibromyalgia: More than just a musculoskeletal disease. American Family Physician, 52(3), 843-852.

Cohen-Katz, J. (2004, Summer). Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and Family Systems Medicine: A Natural Fit. Families, Systems & Health, 22(2), 204-207.

Cook, D., Lange, G., Ciccone, D., Liu, W., Steffener, J., & Natelson, B. (2004, Feb). Functional imaging of pain in patients with primary fibromyalgia. The Journal of Rheumatology, 31(2), 364-378.

Davies, C. (2001). The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide for Pain Relief.Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

De Stefano, R., Selvi, E., Villanova, M., Frati, E., Manganelli, S., Franceschini, E. et al. (2000, Dec). Image analysis quantification of substance P immunoreactivity in the trapezius muscle of patients with fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology, 27(12), 2906-2910.

Ebell, M., & Beck, E. (2001, May). How effective are complementary/alternative medicine (CAM) therapies for fibromyalgia? Journal of Family Practice, 50(5), 400-402.

World Health Organization. (2004). FAQ on ICD. Retrieved 10 August 2004, from http://www.who.int/classifications/help/icdfaq/en/. Forbes, D., & Chalmers, A. (2004, Jun). Fibromyalgia: Revisiting the Literature. Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association, 48(2), 119-132. Gowers, W. (1904). Lumbago: Its lessons and analogues. British Medical Journal, 1, 117-121.

Gracely, R., Petzke, F., Wolf, J., & Clauw, D. (2002, May). Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46(5), 1333-1343.

Hench, P. (1976). Nonarticular Rheumatism, Twenty-Second Rheumatism Review: Review of the American and English Literature for the Years 1973 and 1974. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 19 (suppl),1081-1089.

Henriksson, C., & Burckhardt, C. (1996). Impact of fibromyalgia on everyday life: A study of women in the USA and Sweden. Disability and Rehabilitation Journal, 18, 241-248.

The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version.(1991). Oxford University Press.

Jonsdottir, I. H. (2000, Oct). Neuropeptides and their interaction with exercise and immune function. Immunology & Cell Biology, 78(5), 562-571.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full Catastrophe Living.New York: Dell Publishing.

Kabat-Zinn, J., Lipworth, L., & Burney, R. (1985, Jun). The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8(2), 163-190.

Kelly, J., & Devonshire, R. (2001/1991). Taking Charge of Fibromyalgia(4th ed.).

Wayzata, MN: Fibromyalgia Educational Systems, Inc. Marek, C. C. (2003). The First Year–Fibromyalgia: An Essential Guide for the Newly Diagnosed.New York, NY: Marlowe & Company.

McComb, R., Tacon, A., Randolph, P., & Caldera, Y. (2004, Oct). A pilot study to examine the effects of a mindfulness-based stress-reduction and relaxation program on levels of stress hormones, physical functioning, and submaximal exercise responses. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine: Research on Paradigm, Practice, and Policy, 10(5), 819-827.

Mountz, J., Bradley, L., & Alarcón, G. (1998, Jun). Abnormal functional activity of the central nervous system in fibromyalgia syndrome. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 315(6), 385-396.

Pellegrino, M., Waylonis, G., & Sommer, A. (1989). Familiar occurrence of primary fibromyalgia. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 70(1), 61-63.

Proulx, K. (2003, Jul/Aug). Integrating mindfulness-based stress reduction. Holistic Nursing Practice, 17(4), 201-209.

Raison, C. L., & Miller, A. H. (2003, Sep). When not enough is too much: The role of insufficient glucocorticoid signaling in the pathophysiology of stress-related disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(9), 1554-1565.

Romans, S., Belaise, C., Martin, J., Morris, E., & Raffi, A. (2002). Childhood abuse and later medical disorders in women: An epidemiological study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 71,141-150.

Sack, K. (2004). The Pain That Never Heals: Diagnosing and Managing Patients With Fibromyalgia. Advanced Studies in Medicine, 4(8), 401-408.

Schaefer, K. M. (2003, May/Jun). Sleep Disturbances Linked to Fibromyalgia. Holistic Nursing Practice, 17(3), 120-128.

Schlenk, E. A., Erlen, J. A., Dunbar-Jacob, J., McDowell, J., Engberg, S., Sereika, S. M. et al. (1998, Feb). Health-related quality of life in chronic disorders: A comparison across studies using the MOS SF-36. Quality of Life Research, 7(1), 57-65.

Smythe, H. (1972). The fibrositis syndrome (nonarticular rheumatism). In J. Hollander (Ed.), Arthritis and Allied Conditions (pp. 767-777). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Smythe, H. (1978). Two contributions to understanding the “fibrositis syndrome.” Bulletin of Rheumatic Disease, 28, 928-931.

Starlanyl, D. (1999). The Fibromyalgia Advocate: Getting the Support You Need to Cope with Fibromyalgia and Myofascial Pain Syndrome.Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Starlanyl, D., & Copeland, M. E. (2001/1996). Fibromyalgia & Chronic Myofascial Pain: A Survival Manual (2nd ed.). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Staud R, Price, D., & Robinson, M. (2004). Maintenance of windup of second pain requires less frequent stimulation in fibromyalgia patients compared to normal controls. Pain, 110(3), 689-696.

Staud, R. (2004, Mar). Fibromyalgia pain: Do we know the source? Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 16(2), 157-163.

Staud, R., Cannon, R., Mauderli, A., Robinson, M., Price, D., & Vierck, C. J. (2003, Mar). Temporal summation of pain from mechanical stimulation of muscle tissue in normal controls and subjects with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain, 102(1-2), 87-95.

Staud, R., & Smitherman, M. (2002, Aug). Peripheral and central sensitization in fibromyalgia: Pathogenetic role. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 6(4), 259266.

Staud, R., & Domingo, M. (2001). Evidence for Abnormal Pain Processing in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Medicine, 2(3), 208-215.

Travell, J., Simons, D., & Simons, L. (1999). Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Van Houdenhove, B., & Egle, U. T. (2004). Fibromyalgia: A Stress Disorder? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 73, 267-275.

Williamson, M. E. (1996). Fibromyalgia: A Comprehensive Approach.US: Walter Publishing Company, Inc.

Williamson, M. E. (1998). The Fibromyalgia Relief Book.US: Walter Publishing Company, Inc.

Wolfe, F., Ross, K., Anderson, J., Russell, I., & Hebert L. (1995, Jan). The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 38(1), 18-28.

Wolfe, F., Smythe, H. A., Yunus, M. o. B., Bennett, R. M., Bombardier, C., Goldenberg, D. L. et al. (1990). Criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: Report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 33(2), 160-72.

Wood, P. B. (2004). Fibromyalgia syndrome: A central role for the hippocampus–A theoretical construct. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain, 12(1), 19.

Yunus, M., Kahn, M., Rawlings, K., Green, J., Olson, J., & Shah, S. (1999). Genetic linkage analysis of multicase families with fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Rheumatology, 26(2), 408-412.